Agarwood, the resinous heartwood of Aquilaria sinensis, a tree native to southern China, is a remarkable natural resource with a rich history and diverse applications. Known in Chinese as ‘chenxiang,’ this aromatic wood has been valued for over 2,000 years in East Asia for its use as incense, traditional medicine, and perfume. This well-sourced article examines its biology, cultivation, chemistry, and uses, offering a detailed look at this unique and intriguing wood.[9]

Aquilaria Sinensis Description

Aquilaria sinensis is an evergreen that typically reaches heights of 5 to 15 meters, though under optimal conditions, some specimens can grow even taller. It features smooth, grayish bark and glossy, oval leaves measuring between 5 and 10 centimeters. The tree also bears small, yellow flowers that appear in clusters during its blooming season. These unassuming blossoms attract pollinators and, once fertilized, give way to fruits that enclose the seeds. Recent research has revealed that these seeds are uniquely adapted for biotic dispersal, attracting hornets that play a crucial role in their distribution and the tree’s natural regeneration.[10] Native to the tropical and subtropical regions of southern China—including Hainan, Guangdong, and Yunnan provinces—this species thrives in warm, humid climates.[1] A key characteristic of Aquilaria sinensis is its ability to produce agarwood, a highly prized resin formed when the tree is damaged or infected.

What is Agarwood?

When an Aquilaria sinensis tree gets injured or infected by things like storms, insects, or fungi, it produces a protective resin. This resin soaks into the tress heartwood over time, turning it into agarwood, a dark, fragrant wood that is used in incense, perfume, traditional medicine, and the creation of decorative carvings and jewelry. Its rarity makes it one of the most expensive woods in the world.[2]

Uses of Agarwood made from Aquilaria sinensis

Incense: Agarwood is made into chips and burned for its aroma, a practice with over 2,000 years of history in China. A charcoal disc is lit until grayish-white and placed in a heat-resistant burner; a small piece (about 1 gram) is set directly on the charcoal for a fast, intense scent release, or placed on a mica plate above it for a slower, hours-long burn—high-resin agarwood burns cleaner and is preferred. In the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE), it was burned as “chenxiang” in temples and wealthy homes, its heavy, woody smoke seen as a link to the divine. By the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), it became a luxury trade good along the Silk Road, reaching Southeast Asia, India, and the Middle East, where its spicy-sweet, camphor-tinged scent enriched Islamic rituals. Buddhist and Taoist monks used it in censers to sharpen meditation focus, as noted in the Compendium of Materia Medica (1578) by Li Shizhen, which also says its rarity made it costlier than gold. “By the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), agarwood had grown so scarce that emperors and nobles burned it to flaunt their status. Today, ethically cultivated agarwood remains a treasured incense, still burned in homes and ceremonies worldwide.”[3]

Perfumery: Agarwood’s use in perfumes began in the Middle East around the 8th century. Traders from China’s Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE) transported it along the Silk Road to Arab markets, where it was steam-distilled into oud oil—a dark, thick liquid extract with a warm, woody aroma enriched by spicy and sweet notes. The process was labor-intensive: resin-rich wood was boiled or steamed and only yielded a small amount of oil. Known as “liquid gold,” this oil became a signature of Islamic perfumery, worn by royalty and burned in mosques. By the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), Chinese elites also distilled agarwood for personal fragrances, texts like the Compendium of Materia Medica (1578) note its pungent aroma was prized but rare. Today, Aquilaria sinensis oud oil remains a cornerstone of high-end perfumery, costing up to $30,000 per kilogram.[12] Modern distillation refines sesquiterpenoids for a smoother scent, and cultivated agarwood from China’s plantations ensures supply, though top-grade oil still comes from aged, resin-dense wood. While many perfumes soften its intensity by blending it with rose or amber, pure oud from sinensis remains a coveted hallmark in high-end perfumery.[4]

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM): Agarwood, known as chenxiang, has been utilized in Chinese healing traditions for over two thousand years for its claimed ability to regulate qi (the vital life energy).

Agarwood has been used to soothe a range of ailments. Traditional practitioners prepared agarwood by finely grinding it or soaking it in alcohol. For digestive discomfort, a modest dose of 1–3 grams in warm water or pill form was believed to ease stomach pain, bloating, and nausea by encouraging the smooth flow of qi through the abdomen. In its role as a natural sedative, a smaller dose (0.3–1 gram) steeped in tea or blended with herbs like ginseng was used to calm the shen (spirit), relieving anxiety, insomnia, and even palpitations. Its anti-inflammatory qualities helped in easing joint pain and chest tightness, with daily decoctions of 1–2 grams (with cinnamon or licorice) to promote circulation and balance. Today, the legacy of this ancient remedy is upheld by rigorous modern standards; quality agarwood must meet the Chinese Pharmacopoeia’s benchmark of at least 0.10% agarotetrol (a bioactive compound that plays a key role in its therapeutic effects). Other traditional healing systems, such as Ayurveda and Middle Eastern herbal medicine, have also valued agarwood for its calming and restorative benefits.[5]

Carvings: The use of agarwood from Aquilaria sinensis in carvings dates back to the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), when artisans began shaping the dense, resin-rich wood into prayer beads, small statues, and decorative items such as boxes or pendants, often adorned with dragons, Buddhas, or floral motifs inspired by Buddhist and Taoist traditions. The wood’s dark streaks and durability made it ideal for intricate details, while its faint, natural aroma added spiritual value; monks and nobles wore these beads to ward off evil, as noted in texts such as the Compendium of Materia Medica (1578) by Li Shizhen. Because harvesting wild trees with high resin content was a slow and labor-intensive process, agarwood carvings became exceedingly rare. By the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), their scarcity had elevated them to coveted status symbols, gifted to elites and proudly displayed in courts. Today, modern artisans produce bracelets, figurines, and ornaments from Aquilaria sinensis trees ethically cultivated in China’s plantations. High-resin pieces are prized; for example, a single bracelet of polished beads can fetch hundreds of dollars, and global demand has grown, especially in Asia and the Middle East, where collectors value both their aesthetic beauty and historical resonance.[6][7]

A Sustainable, Ethical Supply of Agarwood?

In nature, agarwood formation is a slow and unpredictable process. A tree might take years to produce usable resin after being wounded by lightning, wind, or microbes, with the resin spreading unevenly to form only small pockets of agarwood amid unaffected white wood.

High consumption and scarce supply have placed Aquilaria sinensis on the IUCN Red List as a vulnerable species, prompting a shift toward sustainable cultivation. Traditional techniques such as chopping the trunk or driving nails into it have given way to advanced methods like the Whole-Tree Agarwood-Inducing Technique (Agar-WIT), in which hydrogen peroxide (that breaks down into harmless water and oxygen) is injected into the tree’s xylem, triggering widespread resin formation in the trunk, branches, and even roots.[7] Alternatively, fungal inoculation with species such as Fusarium, Trichoderma, and Neurospora mimics natural infection to stimulate resin production. Using these methods, high-quality agarwood can be harvested within 4–6 months using Agar-WIT or within 6–12 months via fungal induction.[11]

China now cultivates over 20 million Aquilaria sinensis trees in plantations located primarily in southern provinces such as Hainan, Guangdong, and Guangxi.[7] These regions offer the tropical and subtropical climates ideal for sustainable resin production, helping to ease pressure on wild forests while consistently yielding high-quality agarwood. Scientists are working to develop methods that boost resin yield and quality by exploring how environmental factors (such as salt levels that affect plant health) and the tree’s natural processes for producing aromatic compounds work together. They are also studying the internal cell signals that trigger resin production.

Agarwood: Chemistry, Scent, and Medicinal Value

The magic of Aquilaria sinensis agarwood lies in its unique chemistry. Two key groups of compounds dominate: sesquiterpenoids and 2-(2-phenylethyl)chromones (PECs). Sesquiterpenoids are volatile compounds—such as eudesmanes and guaianes—that lend agarwood its signature woody, balsamic aroma. Meanwhile, PECs, which include important substances like agarotetrol and flindersia-type chromones, are linked to the resin’s medicinal effects.

The balance between these compounds shifts depending on the induction method: mechanical wounding tends to boost sesquiterpenoid production, while fungal or hydrogen peroxide induction enhances PEC levels.

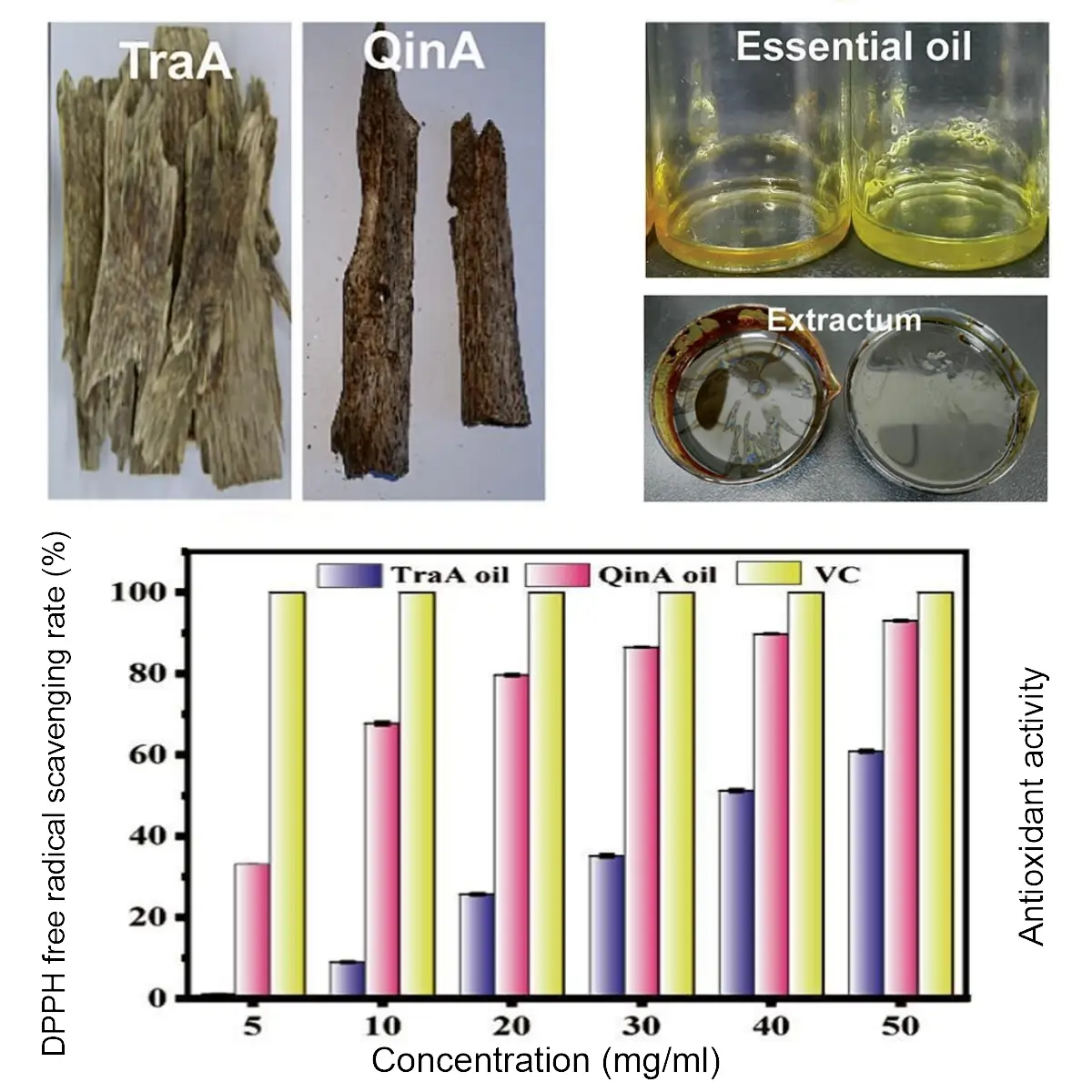

The chemical composition of agarwood can vary significantly. For example, the chart shows an analysis of two differnt varities of agarwood harvested from Aquilaria sinensis, TraA (a traditional agarwood) and QinA (Qinan agarwood). As shown in the chart, the antioxidant activity of the QinA sample is significantly higher than the TraA.[13]

Additional components, such as other aromatic compounds, steroids, and fatty acids, are detected using techniques like gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). High-quality agarwood chips from Aquilaria sinensis often exceed the Chinese Pharmacopoeia’s standards, with the portion of extractable resin—compounds that dissolve in alcohol—comprising no lest than 10% of the chip’s dry weight in cultivated samples.[7] Factors such as induction technique, harvest timing, and the overall health of the tree all influence the final chemical profile.[8]

Sources:

- Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H., & Hong, D. Y. (Eds.). (2007). Flora of China: Volume 13: Clusiaceae through Araliaceae. Science Press; Missouri Botanical Garden Press.

- Harvey-Brown, Y. 2018. Aquilaria sinensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T32382A2817115. Accessed on 25 February 2025.

- Li, S. (2003). Compendium of Materia Medica (Bencao Gangmu) (F. X. Luo, Trans.). Foreign Languages Press. (Original work published 1578)

- Al-Harrasi, A., Rehman, N. U., Khan, A. L., & Al-Rawahi, A. (2019). The chemistry and culture of oud. Springer Nature.

- Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission. (2020). Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China (Vol. 1). China Medical Science Press.

- Schafer, E. H. (1963). The golden peaches of Samarkand: A study of T’ang exotics. University of California Press.

- Liu, Y. Y., Chen, D. L., Wei, J. H., Feng, J., Zhang, Z., & Yang, Y. (2019). Whole-Tree Agarwood-Inducing Technique (Agar-WIT): A novel method for agarwood production. Industrial Crops and Products, 139, 111511.

- Naef, R. (2011). The volatile and semi-volatile constituents of agarwood: The magic of scent. Flavour and Fragrance Journal, 26(2), 73–87.

- Ng, L. T., Chang, Y. S., & Kadir, A. A. (1997). A review on agar (gaharu) producing Aquilaria species. Journal of Tropical Forest Products, 2(2), 272–285.

- Peakall, R., & Bohman, B. (2022). Seed dispersal: Hungry hornets are unexpected and effective vectors. Current Biology, 32(15), R836–R838.

- Wang, Z., Zhou, G., Chen, J., Miao, X., Xia, Y., Du, Z., & Liu, J. (2024). Research on using Aquilaria sinensis callus to evaluate the agarwood-inducing potential of fungi. PLoS One, 19(12), e0316178.

- Alamil, J. M. R., Paudel, K. R., Chan, Y., Xenaki, D., Panneerselvam, J., Singh, S. K., Gulati, M., Jha, N. K., Kumar, D., Prasher, P., Gupta, G., Malik, R., Oliver, B. G., Hansbro, P. M., Dua, K., & Chellappan, D. K. (2022). Rediscovering the therapeutic potential of agarwood in the management of chronic inflammatory diseases. Molecules, 27(9), 3038.

- Ma, S., Yan, T., Chen, Y., & Li, G. (2024). Chemical composition and bioactivity variability of two-step extracts derived from traditional and “QiNan” agarwood (Aquilaria spp.). Fitoterapia, 176, 106012.